When you think about dangerous animals, big or poisonous creatures probably come to mind. But in fact, mosquitoes are one of the most deadly animals in the world.[1]

That’s because mosquitoes can transmit a range of diseases which are of major public health concern globally.

Most Canadians think of these diseases carried by mosquitoes, called mosquito-borne diseases (MBD), as being limited to warm southern climates, like malaria or dengue fever. While it is true that they are far more common in the tropics, warming temperatures and increasing precipitation under climate change in Canada are expected to increase the presence of some MBD right here at home

“[Mosquitoes] are very sensitive to climate, in particular temperature and precipitation,” says senior scientist and mathematical modeller at the Public Health Agency of Canada, Dr. Victoria Ng. Ng explains how climate change is expected to bring warmer temperatures and changes in precipitation which will affect mosquitoes.

Watch: What's the Buzz: Mosquito-borne diseases and climate change

More mosquitoes in a warmer, wetter world

Mosquito-borne diseases are increasing under climate change. Over the last 20 years, MBD in Canada have increased by 10%, largely due to climate change.[2]

That’s because mosquito life cycles, reproduction, and feeding depend on temperature, precipitation, and land-use.[3] So the impacts of climate change can change the habitat, seasonality, and distribution of mosquitoes that carry diseases.

As Manitoba epidemiologist Dr. Richard Rusk explains, longer seasons can lead to more generations of adult mosquitoes each year. If there is a virus present in the mosquito population early on in the season, it can be amplified during this process, ultimately leading to more people getting sick. “If there’s a lot more people getting exposed, that means the numbers [of people getting sick] automatically end up going up,” Rusk notes.

Climate change doesn’t only impact the mosquitoes themselves. It also affects the animals that carry the disease, the microorganisms that cause the disease, and how those microorganisms move between animals and mosquitoes. This makes it difficult to predict changes in MBD under climate change.

Read More: How do mosquitoes transmit diseases?

The microorganisms (also called pathogens) that cause mosquito-borne diseases are naturally found in environments within animal hosts. When mosquitoes, which require blood for their development, bite an infected animal host, they can become infected with a virus. After becoming infected it takes the mosquitoes a few days to replicate the virus to be able to pass it on to another person when they take their next feed.

“With climate change, as it gets warmer, this extrinsic incubation period will become shorter, which means they will be able to infect more humans and faster because it takes them less time to become infectious and to transmit to humans,” Ng says.

In addition to increasing the number of mosquitoes, climate change may also bring new mosquito species northward into Canada. And with new species comes the potential for new diseases.[4][5]

Read More: Mosquito species in Canada

Not all mosquitoes are the same. In fact, there are about 80 different species of mosquitoes in Canada.[6] Of these, only a few can carry bacteria or viruses that cause disease.

Two of the few mosquitoes in Canada that can transmit disease are Culex pipens and Culex tarsalis. These Culex species are responsible for most of the West Nile Virus infections across Canada. Culex pipens are found in mostly urban settings while Culex tarsalis prefer rural environments.[7] Under climate change it is expected that these species will expand their range northward into southern Quebec, southern Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as increase in population.[8]

A different group of mosquitoes, the Aedes mosquitoes, are of particular public health importance because of the exotic diseases they can carry such as Chikungunya and Zika virus. “We've recently seen the introduction of Aedes albopictus that came in slowly and gradually from the US moving north into Canada” says Ng. “In 2017, there was a large population that was found. [Although only] in a very limited part of southern Ontario, it has become established [in Canada]. That is something we can anticipate with climate change, to see more of these events happening”

Aedes mosquitoes are generally tropical and subtropical species but with climate change it is expected that much of southern Canada will become suitable habitat.[9][10] They are already considered established in the Windsor region of Ontario.[11] This indicates a higher possibility of local transmission of exotic diseases such as Chikungunya during times of the year when mosquitoes are present.[12] The table below outlines some of the main species that can transmit MBD in Canada.

| Mosquito Species | Diseases they can carry | Currently in Canada? | Impacts under climate change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culex pipiens | West Nile Virus and St. Louis Encephalitis | Yes, mostly in urban areas | Spread northward, increase in population and transmission season[13] |

| Culex tarsalis | West Nile Virus, St. Louis Encephalitis and Western Equine Encephalitis | Yes, mostly in rural areas | Spread northward, increase in population and transmission season[14] |

| Aedes albopictus (Asian Tiger Mosquito) | Dengue, Yellow fever and Chikungunya viruses | Yes, only in Windsor, Ontario region | Spread northward[15] |

| Aedes Aegypti (Yellow fever mosquito) | Dengue, Chikungunya, Zika virus and Yellow fever viruses | No | Spread northward[16] |

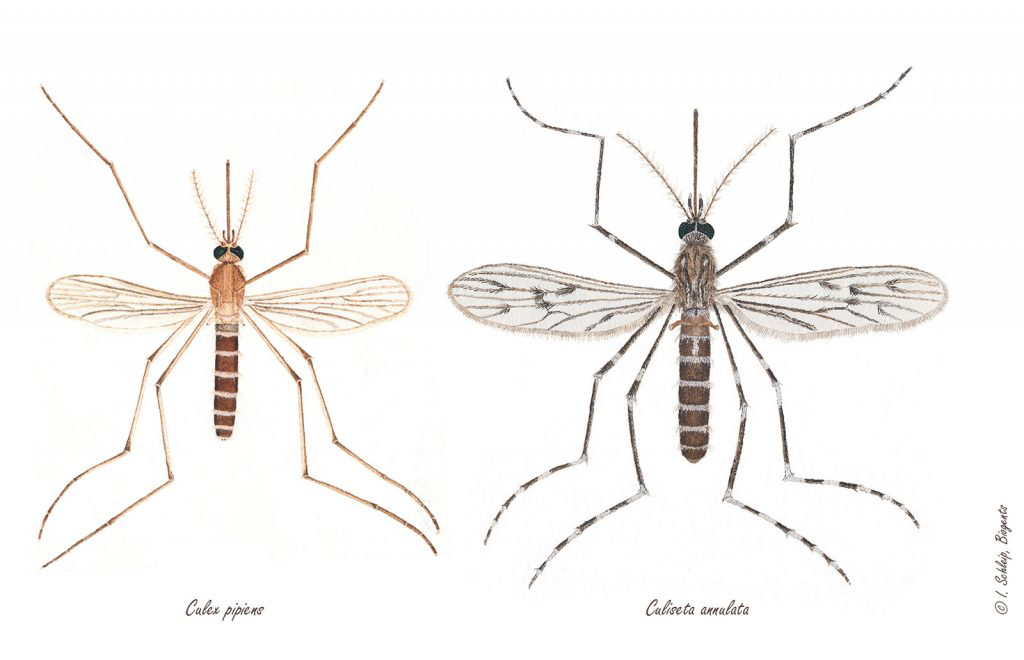

Mosquitoes look very similar but the different markings as well as other characteristics help professionals differentiate. The different marking on their head is the main way to tell Aedes mosquitoes apart. Aedes albopictus have a white stripe while Aedes aegypti have two stripes along with marking on the side.

Aedes aegypti (left) and Aedes albopictus (right) mosquitoes. (Photo credit: Frank Hadley Collins/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Culex mosquitoes are harder to tell apart. Their main identifying factor is the length of their limbs and the white stripes on their limbs.

Culex mosquito species (Photo credit: https://us.biogents.com/wp-content/uploads/Culex-pipiens-Culiseta-annulata-Schleip-Biogents-1024x660.jpg

West Nile Virus

West Nile Virus (WNV) in humans was first introduced to Canada in Ontario during 2002[17] and has since become something we see year after year. The virus is carried primarily by birds, and transmitted to humans when a mosquito bites an infected bird and then bites a person. In rare cases, it can also be spread by blood transfusion or organ transplantation.

Read More: West Nile Virus

Most cases of West Nile Virus (WNV) do not present any symptoms, and therefore go undetected. In some cases, people experience mild symptoms such as fever, headache, rash, bodyache, and swollen lymph glands, and in very rare cases (less than 1%) severe symptoms which affect the brain.[18]

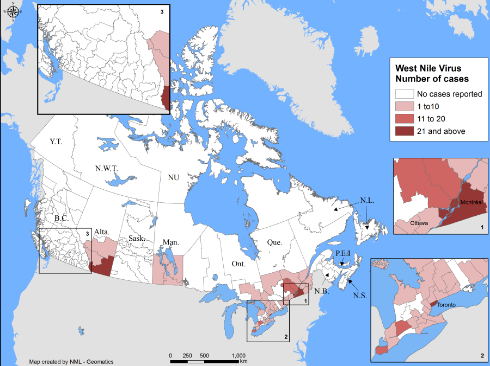

Because of the often asymptomatic nature of the disease, the true WNV infection rate in Canada is unknown. Reported cases vary geographically and year to year, climate conditions of the region and of the year impact how many cases occur. The map below shows the number of documented cases in 2018. The darker red zones represent the areas with the most diagnosed cases with the white zones having no reported cases.

Source: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/west-nile-virus.html)

Climate change is expected to cause more outbreaks of WNV in Canada. Outbreaks have been linked to mild winters, prolonged droughts, and heat waves - all of which are more likely under climate change.[19] Increases in mosquitoes with MBD will have the biggest effect on people in urban areas, due to the higher population density in the environments.

In the Canadian Prairies, one of the most common regions for the disease in North America, research has documented an increase in WNV largely due to increased temperatures and more variable rainfall in recent years.[20]

Winnipeg resident Chris Knight knows West Nile Virus first-hand. He contracted it in Northwestern Ontario almost a decade ago, and the experience is still with him today.

Read More: Chris Knight’s experience having West Nile Virus

Chris Knight, a Winnipeg resident, was out with his father on their lake property in Kenora surveying land for their cabin when he believes he got West Nile Virus. “I should have been wearing some DEET or some bug repellent or something, because I'm fairly certain that that was the moment that I picked up West Nile,” he says. About a week later he started feeling unwell. “I started getting really frustrated. I couldn't quite place it.” he describes. “The next morning it was worse. I started feeling fatigue, like fluey.” Upon returning from the trip he visited the doctor and got blood work done. Within a few days it was confirmed that he had contracted West Nile Virus.

Diagnosing West Nile Virus can be tricky as most people experience mild or no symptoms at all. For those who do experience symptoms, recovery can take a few weeks or even months.[21] The virus can cause symptoms such as headaches and confusion, which are some of the symptoms Chris experienced.

“It probably took about six months to just stop being frustrated [with my inability to do tasks I had much experience with] . And then probably another six months to feel like I was back up to a normal level,” Chris explains.

Since having this experience, Chris is more cautious when going outdoors. “That was definitely a memorable moment. So when I find myself in similar situations, it's hard to not think back like, "Well, having had that experience, let's try not to do that again." And yeah, it has changed my behavior.”

Read More: Ways to protect yourself against mosquito-borne diseases

As mosquito-borne diseases become increasingly common, it’s important to take the appropriate measures to protect yourself. Some ways you can reduce your risk are by wearing bug repellent, wearing long sleeves and long pants when outdoors, avoiding going out when mosquitoes are most active (dusk and dawn), removing standing water around your home (in tires, flower pots, containers, etc.), and ensuring windows have properly fitting screens.[22]

Mosquito-borne diseases can also be contracted while travelling. “Climate change isn’t going to just impact Canada, it’s going to impact all the countries where these diseases are circulating,” says Ng. “We like to travel, we bring back infections. If the diseases are transmitted more rapidly in the countries of origin, then Canadians are going to be coming back with those travel related cases more frequently.” Talking to your healthcare provider prior to travelling about how to protect yourself is recommended.

Public health responses and adaptation

While the risks of mosquito-borne infectious diseases are relatively low in Canada compared to other parts of the world where there are warmer, more humid climates, impacts of climate change are increasing threats of existing and new mosquito-borne and other infectious diseases.[23] It is not only the impacts of these diseases directly that we must prepare for, but the other potential impacts of climate change which may affect our ability to adapt and control these diseases.[24]

Under climate change, events such as wildfires, floods, and heatwaves are expected to increase. The compounding health impacts from climate related events could overwhelm our healthcare system. We must prepare for the challenges that will come with a changing climate.

“It’s very current and it’s not something that’s going to go away. Climate change is an issue and it will be for our children,” says Ng. “Especially because I do have children, I know it is a problem we’re going to pass on to them. So I think it is important that we do tackle it now, address it and try to get a sense of what the risks are, and to also get them involved as well.”

Taking action at all levels, from the individual to international, is essential to ensuring a safe future climate and protecting human health. It is important to both act to reduce our emissions to slow the impacts of climate change, as well as to adapt to the health risks, such as MBD, which we know will be increasing in the coming decades.

References

- World Health Organization. “Vector-borne diseases” https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/vector_ecology/mosquito-borne-diseases/en/

- Ludwig, Zheng, Vrbova, Drebot, Iranpour, and Lindsay. 2019. Increased Risk of Endemic Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Canada Due to Climate Change. Canada Communicable Disease Report 45:91–97. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v45i04a03.

- Wudel, and Shadabi. 2016. Mosquito-Borne Disease in the Americas. Rapid Review | NCCID. https://nccid.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/07/RapidReviewClimateMosquito-EN.pdf.

- Ng et al. 2017. Assessment of the Probability of Autochthonous Transmission of Chikungunya Virus in Canada under Recent and Projected Climate Change. Environmental Health Perspectives https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP669

- Ogden, N.H., Milka, R., Caminade, C. et al. Recent and projected future climatic suitability of North America for the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus. Parasites Vectors 7, 532 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-014-0532-4

- https://cwf-fcf.org/en/resources/encyclopedias/fauna/insects/mosquito-1.html

- Ludwig et al. 2019.

- Wudel and Shabadi, 2016.

- Khan, Ogden, Fazil, Gachon, Dueymes, Greer, and Ng. 2020. Current and Projected Distributions of Aedes Aegypti and Ae. Albopictus in Canada and the U.S. Environmental Health Perspectives 128. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP5899.

- Ogden, N.H., Milka, R., Caminade, C. et al. Recent and projected future climatic suitability of North America for the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus. Parasites Vectors 7, 532 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-014-0532-4

- Windsor-Essex County Health Unit. "Aedes albopictus mosquito". Accessed from: https://www.wechu.org/z-health-topics/aedes-albopictus-mosquito

- Ng et al. 2017. Assessment of the Probability of Autochthonous Transmission of Chikungunya Virus in Canada under Recent and Projected Climate Change. Environmental Health Perspectives https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP669

- Hongoh, Berrang-Ford, Scott, and Lindsay. 2012. Expanding Geographical Distribution of the Mosquito, Culex Pipiens, in Canada under Climate Change. Applied Geography 33:53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.05.015.

- Chen, Jenkins, Epp, Waldner, Curry, and Soos. 2013. Climate Change and West Nile Virus in a Highly Endemic Region of North America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10:3052–71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10073052.

- Khan SU, et al 2020.

- Khan SU, et al 2020.

- Public Health Ontario. 2015. Vector-Borne Diseases 2014 Summary Report. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/V/2015/vector-borne-diseases-2014.pdf?la=en&rev=ee00e48e789e4ccca0ecbda2f7c4e7fe&sc_lang=en&hash=2E25B35A96D05D3EEDA63BA5B474548A.

- Public Health Ontario, 2015.

- Austin, Ford, Berrang-Ford, Araos, Parker, and Fleury. 2015. Public Health Adaptation to Climate Change in Canadian Jurisdictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12:623–51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120100623.

- Paz. 2015. Climate Change Impacts on West Nile Virus Transmission in a Global Context. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0561.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment”. https://www.cdc.gov/west-nile-virus/symptoms-diagnosis-treatment/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/symptoms/index.html

- Government of Canada. “Prevention of West Nile virus.” https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/west-nile-virus/prevention-west-nile-virus.html

- Ng V, Rees EE, Lindsay LR, Drebot MA, Brownstone T, Sadeghieh T, Khan SU. Could exotic mosquito-borne diseases emerge in Canada with climate change? Can Commun Dis Rep 2019;45(4):98–107. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v45i04a04

- Ogden, and Gachon. 2019. Climate Change and Infectious Diseases : What Can We Expect ? 45:76–80.

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Mosquito-borne diseases and climate change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/mosquito-borne-diseases-and-climate-change

.png)