Shawn Bailey and Lancelot Coar are trying to change the way architecture students think about the connection between climate change, Indigenous Knowledges, and design. Associate Professors in the Department of Architecture at the University of Manitoba, Bailey and Coar guide students on their journey to becoming practicing architects. Every year Coar and Bailey teach a design course for 4th year architecture students and, increasingly, they are trying to break the mold of what and how students are learning.

In recent years, students have taken on designs that address climate change, while incorporating different ways of knowing into their approach. “Through long and sustained partnerships with communities, we use this studio as an opportunity to expand our own understanding of what's important.” Coar explains. The course teaches students that architecture is more than simply designing buildings. It challenges students to consider architecture from a more holistic lens, exploring questions of why and how buildings are designed, and for who. Respecting perspectives of community and land in the process of design, students are encouraged to think on “How can we be better allies, and assist in the way of supporting Indigenous voices, the Indigenous ways of thinking that can enhance the way that we understand how design works.”

Architects are one of many professions that First Nations communities work with to support the design and development of infrastructure. Along with planners and engineers, architects are often referred to as practitioners, and like the graduating students in Coar and Bailey’s class, they receive their credentials from academic institutions such as universities and colleges.

There is an increasing awareness that these practitioners have been trained in programs that teach western scientific methods, sometimes referred to as mainstream knowledge or western science. These methods often emphasize quantitative and siloed approaches that view the environment as a resource to extract from and conquer, undervaluing the oral traditions, storytelling, and cultural practices and language essential to Indigenous communities. [1]

The Western style of learning is where Coar and Bailey are trying to push boundaries. “We're challenging [Western and colonial systems] to expand to include other ways of knowing and being that make the work more accountable... What we're trying to do is to find a way where these things complement each other.” Learning and practicing in new ways and from new perspectives is how Coar and Bailey believe we can better address complex challenges, such as climate change and reconciliation.

Decolonizing how we learn

“Although western science can describe the natural world, it does not speak to how to live with it.” McGregor, 2018

Coar and Bailey are not the only educators that are taking a different approach to learning. Education systems across the country are making efforts to decolonize how students are trained and taught. In the early 2000’s, the concept of Two-Eyed Seeing was developed by Mi’kmaw Elders Albert and Murdena Marshall, along with Dr. Cheryl Bartlett at Cape Breton University. The term means “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all.” [2]

Educators such as Coar are consistently trying to bring these principles into their teaching approaches. Coar acknowledges that current practices for infrastructure design are limiting and need to be reimagined to focus on the importance of relationship building with people and the land. “Design practice is a very limited tool to produce meaningful change because it usually refers to designing shapes, objects and systems. But the reality is, those do not mean much or are not going to last very long without having the cultural resilience and relationships that are necessary to maintain it and give it meaning over time.”

The Department of Architecture at the University of Manitoba was guided in the process of integrating Indigenous knowledges into their teaching, education, and practice by late Elder in Residence Valdie Seymor. Elder Seymour’s wisdom articulates the shift in perspective needed for students to approach infrastructure design and development through an Indigenous lens. “You can teach them that the big piece is learning how to look at a forest. Not to see a tree as a 2x4 but see the whole history of that space and all of the other life forms and all of the other possibilities. It also includes story and spirit and whole ecosystems and if young people understand that, that changes the game.”

The importance of story, relationship, and spirit are essential in learning through an Indigenous lens. As Elder Albert Marshall puts it “ Everything was story ... where you have the responsibility to listen and reflect. This is a much more profound way of learning because you have the opportunity for a relationship with the knowledge.” This approach to learning places emphasis on students creating a personal connection and relationship with the knowledge being shared. “If a sense of relationship with the knowledge is not identified…. The understandings have not been assimilated; the head and heart have not been connected.” [3]

To address complex topics like climate change, decolonization, and infrastructure, educators such as Coar are evolving how they work with students. Previous approaches were centered on instructors “having” knowledge that they share with students. These are being replaced with critical thinking and systems thinking approaches. “We're showing them a version of how practice could work…We're trying to find better ways of working. We're trying to give students the tools necessary to dismantle systems that are not able to meaningfully engage with the scale, scope and speed of change necessary to address the global challenges.” Coar also notes that this change is not just driven by educators. “Students already understand there are profound problems across the planet. They understand the challenges are of another scale that we've never encountered before. But they're hungry for ways of working…which lead to more resilient, equitable and inspiring ways of building the future together.”

These shifts in approaches to teaching, learning, and working together are done with the intent of designing and building infrastructure that better meets the needs of the people using it. The changes go much deeper than the designs on paper or the buildings that are constructed. Elder Seymour explains the real change that needs to occur. “I think it's us that has to change…it has to start with people…It has to do with everything that's alive, that has a spirit.”

Read More: KCA video

Relationships for Change: Kenora Chiefs Advisory and University of Manitoba Faculty of Architecture - The Architecture department at the University of Manitoba is taking a novel approach to teaching the importance of relationship building when working in First Nation communities with a “ground up” approach rooted in the land-based teachings of First Nations. Capturing this approach demonstrates how emerging practitioners are being equipped with these process-based skills of cogeneration and collaboration.

Read More: The 5 principles for decolonizing the design process

“How can we undertake our work in a way that creates meaningful collaboration and knowledge cogeneration with First Nations ? And how can students entering these fields of practice be taught to use decolonized processes that lead to more equitable, diverse and inclusive practices?”

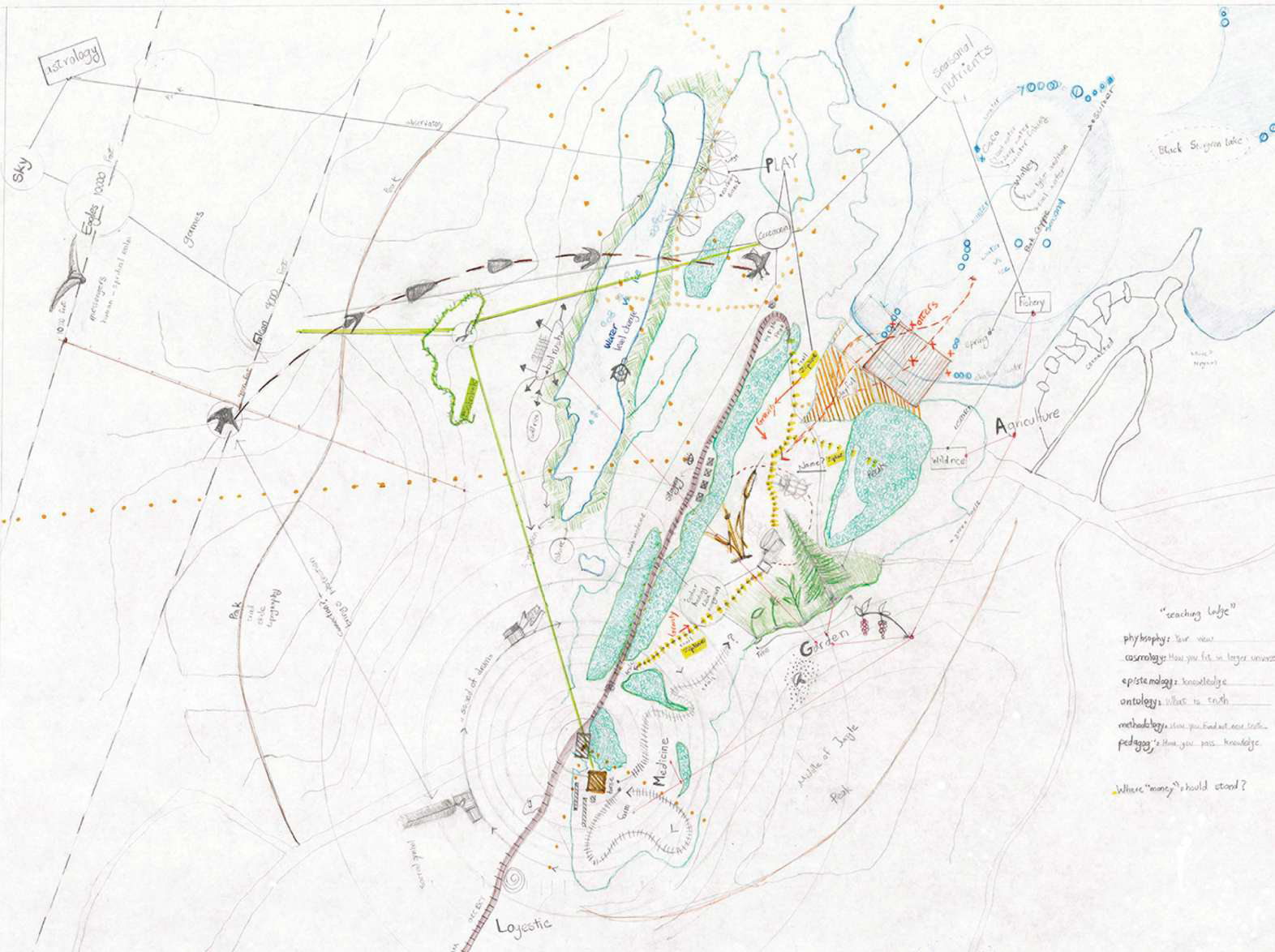

Bailey and Coar have been actively exploring these fundamental questions for years. Collaboration, relationship development, and cultivating awareness of shared learning experiences have led to the development of five principles to help guide this process. These principles emphasize attention to place, intuition, listening, visions, reciprocity, and sharing a good story. [1]

Indigenizing design is about the process that is used to learn, and not the content itself. Coar and Bailey have learned this through the guidance of Elder Seymour, and the communities they have developed meaningful and trusting relationships with.

Coar notes that these principles “are meant to be a complement to conventional practice. And they include Indigenous ways of understanding where we are, when we are, what our responsibilities are, how to trust our own internal process and our intuition, how to deliver a project that is meaningful, how to take responsibility for what we do.”

The 5 principles for decolonizing the design process are shared by Bailey, Coar, and Black in several pieces of writing, and are summarized below. It is important to note that there is not one correct path or singular way of doing this. [1]

Da na ka mi gad - IT TAKES PLACE, AND HAPPENS IN A CERTAIN PLACE. This principle centers on the importance of understanding the significance of place. This is done by fostering relationships with the Land and people.

An do tan - LISTEN FOR IT; WAIT TO HEAR IT. Active listening, conversation, and creativity can unveil unique opportunities, and develop relationships. This principle underscores the significance of relationships through storytelling, fostering a close-knit bond with the community and the environment.

Ba waa ji gan - A DREAM, A VISION. Vision and direction are created through purposeful collaboration. Constantly evolving relationships should guide the vision and direction of any project.

Meshk wad - IN TURN, IN EXCHANGE. We all have gifts to share. We can learn from each other as we take turns sharing these gifts. This exchange guides project and design.

Naa go toon - MAKE IT SHOW, REVEAL IT. This principle acknowledges that the real significance of a project is through the story it can tell. Stories facilitate reflection, learning, and growth.

Collaboration with Kenora Chiefs Advisory

In the 2023 / 2024 school year, Coar and the students in his course partnered with the Kenora Chiefs Advisory (KCA), an organization that focuses on providing health and social services for the seven Northern Ontario communities it is affiliated with. KCA had recently purchased a property just north of Kenora, Ontario with plans to develop the land into a camp that connects the communities, in particular the youth, to the culture, ceremonies, and teachings of their Anishinaabe ancestors.

The design course was offered in two one-term intensive studios that emphasized the importance of building partnerships with communities. Students connected with community members and knowledge keepers to develop project ideas that were grounded in place, and reflected the needs and values of the community. These relationships and the sharing of knowledge and story were foundational to the course.

Through careful listening, with both their heart and mind, the students heard the various dreams and visions from KCA for the future of their camp. Based on this, the students developed projects that spoke to those visions. From this, four main themes emerged – Food Sovereignty, Housing & Community, Cultural Preservation, and Play as Medicine. From these themes students worked to develop unique projects based on certain locations of the property. Each project was shaped through a story and sought to build on the histories and hopes for the future of the KCA project. The site visits and cultural activities the students experienced at KCA were instrumental to the stories their projects were based on and guided the architectural design decisions. In many ways, these stories were the foundations of the entire design journey. The Knowledge carriers, elders, youth, and staff at KCA were essential in helping make the students feel welcome and safe to learn about the stories at KCA. It was through their loving and generous energy and efforts that the students felt a part of something bigger, something meaningful.

Jyles Copenence is the cultural educator at the camp. He works closely with the students and youth passing on teachings that he had learned from working on the land, in the classroom, and lodges. Jyles is clear that any development on the site needs to be driven by the needs of the communities. “We wanted to make sure that the designs of the building reflected the culture, that it reflected the food, that it reflected the ceremonies that we have in this area. So, for instance, our cultural area will have a roundhouse where we can have powwows, where we can have feasts, but also we wanted to make it where it can accommodate schools, where it can accommodate universities and colleges to come out here and learn.”

The project at KCA is an example of how practitioners and the schools that teach them are learning to build relationships to integrate many knowledges into their practice. These relationships for change, and learning and seeing from different perspectives, are one step on the journey to designing infrastructure that meets the needs of communities and addresses the challenges of a changing climate.

References

- Bailey, S., Black, H. and Coar, L. Decolonizing the Design Process with Five Indigenous Land-Based Paradigms. Canadian Architect. May 2021. https://www.canadianarchitect.com/decolonizing-the-design-process-with-five-indigenous-land-based-paradigms/

- Bartlett, C., Marshall, M. & Marshall, A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J Environ Stud Sci 2, 331–340 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

- Marshall and Bartlett. Two-eyed Seeing for Environmental Sustainability. Presentation. Integrative Science. College for Sustainability, Dalhousie University. September 23rd, 2010. http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/articles/2010September-Marshall-Bartlett-Integrative-Science-Two-Eyed-Seeing-environment-sustainability-Aboriginal.pdf

- McGregor, D. From ‘Decolonized’ to Reconciliation Research in Canada: Drawing from Indigenous Research Paradigms. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 2018, 17(3): 810-831. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v17i3.1335

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Relationships for Change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/relationships-for-change

.png)