“We want to take a look at how we can build better information for First Nations.”

Climate change planning needs to be done by the First Nation community, for the First Nation community. That’s what Elmer Lickers believes is the key to success. Elmer Lickers is Mohawk, a member of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. He is also a senior advisor at the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation (OFNTSC). Lickers and his team work with communities on a program called the First Nations Infrastructure Resilience Toolkit (FN-iRT), a First Nations specific approach to climate change risk assessment for infrastructure and asset management. (Learn more about the Basics of Climate Risk Assessment

“[It] does asset inventory, asset management, climate risk assessment. It’s a planning tool for you to look at ‘What are your needs today? What are your needs 100 years from now? And how is climate going to be a part of that need?’.”

“We want to take a look at how we can build better information for First Nations.” - Elmer Lickers

The toolkit takes an established climate risk assessment and asset management program and includes a crucial element: community voices.

“[We’re] taking a look at how we can bring not only the technical aspects in First Nations, looking at their infrastructure, but bringing the cultural aspects, and the traditional aspects into their process.”

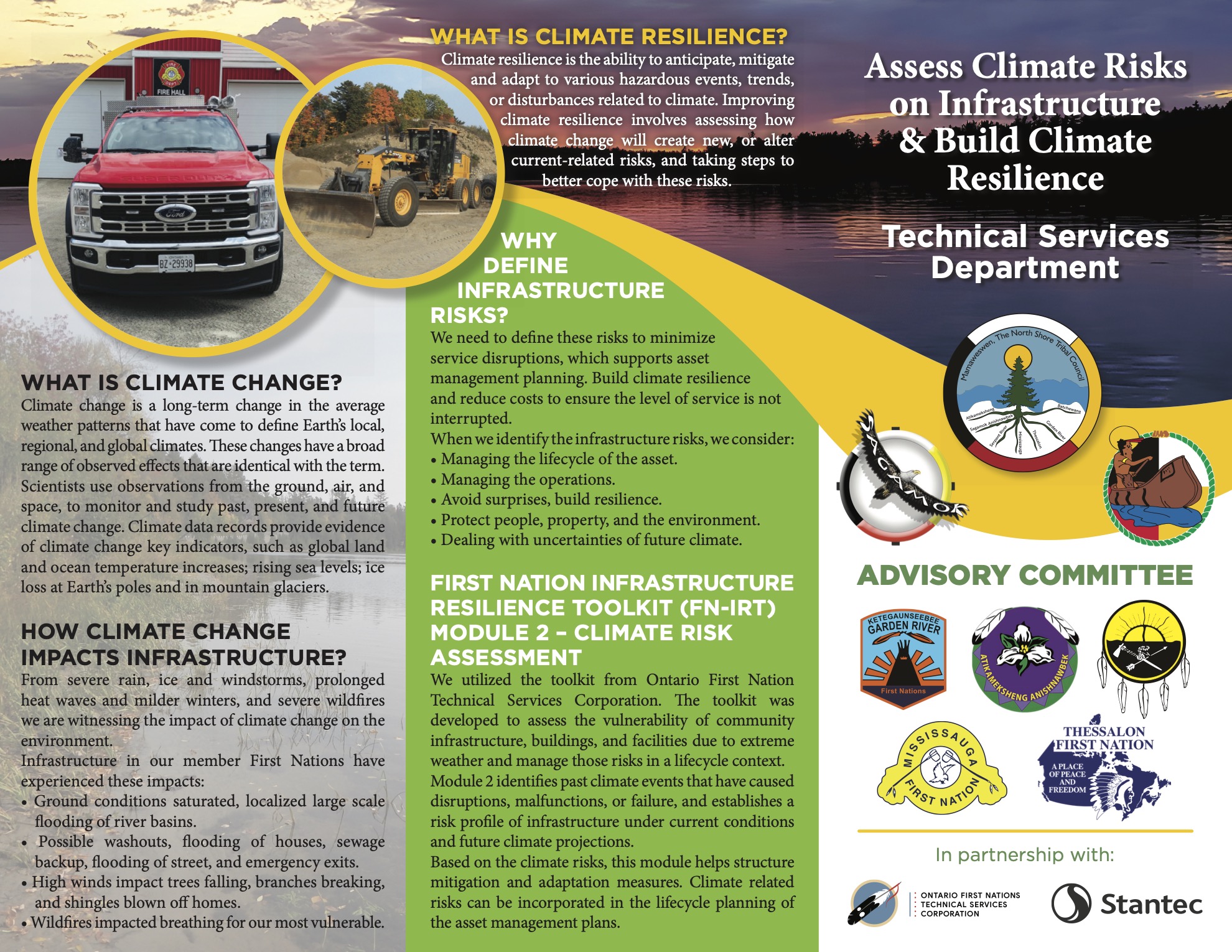

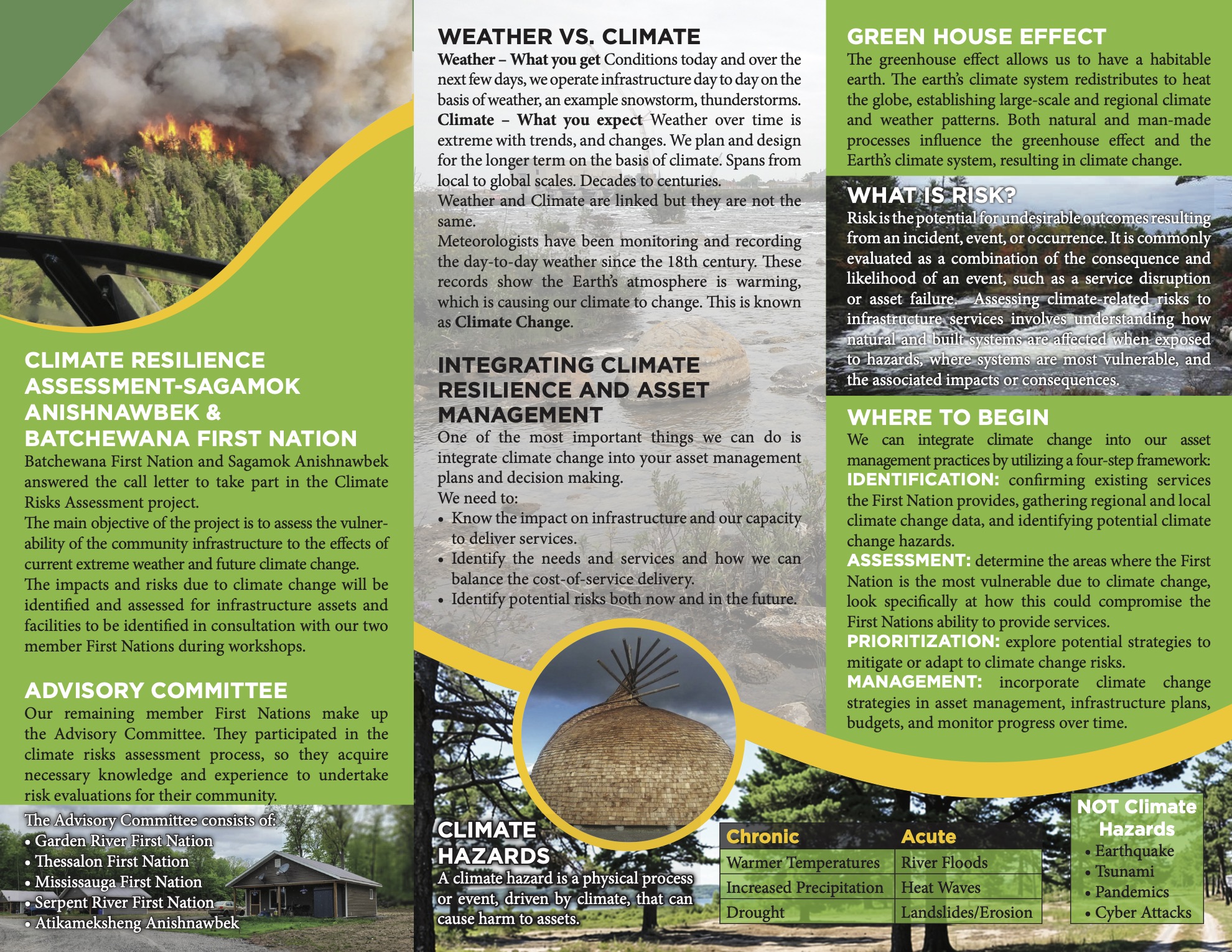

Throughout 2024 Elmer and his team at OFNTSC, alongside an engineering consulting firm, Stantec, worked with Mamaweswen, the North Shore Tribal Council (NSTC) on climate change planning. NSTC represents (7) First Nation communities along the North Shore of Lake Huron in Ontario, and two of these communities, Batchewana and Sagamok Anishnawbek, participated in the climate risk assessment program. The communities spent several days going through the FN-iRT process, taking an inventory of their infrastructure and assets, documenting how climate change is impacting them, and how they can plan for it.

The FN-iRT is one of a number of programs that are focused on helping First Nations plan for climate change. What makes these processes effective? They focus on the strengths and local knowledge of the community.

Planning with Community in Mind

Climate change is a global issue that is experienced at the local level. Extreme climate-related events like heatwaves, flash floods, high winds, and drought affect the people and buildings in communities, and the land and wildlife found around them. Communities are at the front lines of climate change, and this first-hand experience means they understand its impacts on their way of life.

“We also wanted community members as stakeholders. We wanted to hear their voices.” Lickers explains. He also emphasizes the importance of reaching everyone in the community. “We wanted not only their technicians, their administrators, but also their elders and their knowledge keepers as a part of the process.”

Lickers knows that in order to develop plans that meet their needs, the lived experiences of the whole community needs to be included in the process. This requires inclusion of youth, elders, knowledge keepers, gender diverse peoples, and 2LGBTQQIA+ in all aspects of planning processes.[For our Futures] An inclusive approach strengthens community planning and cohesion.

To reach as many people as possible, NSTC and the OFNTSC team made the process approachable, fun, and inclusive.

OFNTSC and NSTC started by reaching out to gather interest. “Phase 1 of that was creating awareness in the communities.” Melissa Shawbonquit is the Infrastructure Specialist with NSTC. Shawbonquit led the coordinating and engagement efforts. “We developed brochures, something simple that we could hand out. It was jam packed full of information, very educational.”

The next step was to bring people together to hear what they had to share. To do this, the team decided to hold an event that would draw people in. In Sagamok Anishnawbek, everyone was invited to a special bingo night, with prizes and a feast, and a little bit of climate risk assessment on the side. Community members were eager to participate, and Lickers and his team were also happy to engage this way. “Mind you it’s Bingo related, that’s fine, we have fun with that!”

Community members came together and discussed the different ways they were experiencing and witnessing climate change. Topics ranged from the changes in migration of wildlife, the deforestation of ash trees and the repercussions for cultural activities and practices, concerns about safety and weather, extreme heat, power outages, and increased stress on volunteer firefighting crews. Using this feedback, it was then up to the core working group, a group of administrators, technicians, and decision-makers, to use this information along with the asset and climate data to evaluate climate risk and make plans to address it.

Working in an inclusive and collaborative way helps set the stage for meaningful planning. “That, to me, brings ownership of the tool to the community, brings a sense of pride that community members were stakeholders in the process.” Lickers expresses the importance of this to the community, as “at the end of the day, it’s relevant to the First Nation.”

Read More: The importance of ash trees

It's not just climate change, it's everything change. Buildings are not the only important things that are impacted by a changing climate. Natural areas such as forests, wetlands, waterways, and the cultural practices that are connected to them are also affected by climate change.

Allen Toulouse, from Sagamok, explains the importance of the ash tree to his community and its connection to cultural practices.

“We’ve seen the devastation of the ash trees, and ash trees in Sagamok are important because there is a whole thing with ash basket making, the ashwood as a tool, one of the prime woods for making bows.” Speaking of an elder in his community, “her art form is making ash baskets, now that’s a whole cultural component that won’t be able to be replicated anymore, because of climate change preventing the winter season from holding off these emerald ash borers.”

Using the right language and understanding what is important to a community ensures planning is done in the right way.

Read more about the impacts of emerald ash borers and other forest pests here.

Power of Community Knowledge

Lickers credits the success of their approach to moving beyond the typical numbers and data, and emphasizing the importance of community knowledge. “If we didn’t bring in that local knowledge and traditional and cultural knowledge into the process, and just stuck with the technical process, I don’t think we would have been as successful.”

Lickers often describes First Nation communities as “filthy rich with data”. He is referring to both the information communities have around their infrastructure and assets, as well as their histories and knowledge of the land. This history and knowledge are often shared in stories and teachings, passed down through generations.

Ronnie-Ann Toulouse recounts some of the lessons she has learned from her father, a trapper that used to spend most of his time out on the land. The lessons in observation, understanding the land and seeing how things are changing are incredibly valuable when discussing the impacts of climate change.

“We always have thunder and lightning in January. It might not have been as bad as it was this year, but in the past you’ll hear it. My father was a trapper, he spent a lot of time observing. The Trappers in those days really knew the seasons, the weather. They really understood that because they were busy living out in the wilderness.

They understood that was normal. In our culture, it tells us that the thunderbirds are coming, and it also teaches you if we are going to have an early spring, or a late spring. That really depends on the colour of that lightning. That’s one of the teachings my father passed onto my family. And the moon and the sun will teach you all these things.”

The importance and value of community information and the weaving of scientific data with local knowledge cannot be overstated. “Good scientific data …. can be useful for our First Nations, at the same time it’s the local knowledge that the First Nations have of what’s happening in their community that is an added value to the data. It’s a win-win world for First Nations to bring the two together”. What Lickers describes is “Two-eyed seeing”, a concept developed by Albert Marshall. This process is an opportunity for learning from both sides through an exchange of knowledges. Read more about Two-eyed seeing in the Relationships for Change” article.

Read More: Weaving Indigenous and Western Knowledge Systems in Practice

In the Northwest Interior of British Columbia, the Gitksan Watershed Authority (GWA) is utilizing western and Gitksan methodologies for the conservation, protection, and management of Salmon habitats.

One of their ongoing projects is creating a background assessment of salmon and salmon habitat in the Kispiox watershed. Their approach uses a combination of technical assessments and community engagement with Gitksan expert voices. These voices speak to the past and present state of salmon populations and habitats in the watershed. The weaving of these methods allow the GWA to identify and understand the cultural importance of specific salmon systems in the region, and highlight long term trends beyond the western scientific data gathering time periods.

The process of weaving Indigenous knowledge and western knowledge systems enhances the robustness of information gathered. This approach can help address complex challenges such as climate change, benefiting both current and future generations.

Communicating in a Meaningful Way

Knowledge sharing in community is not often confined to pen and paper. Oral traditions and teachings are a large part of many First Nations’ cultures. Planning should include different ways of recording and communicating information and knowledge.

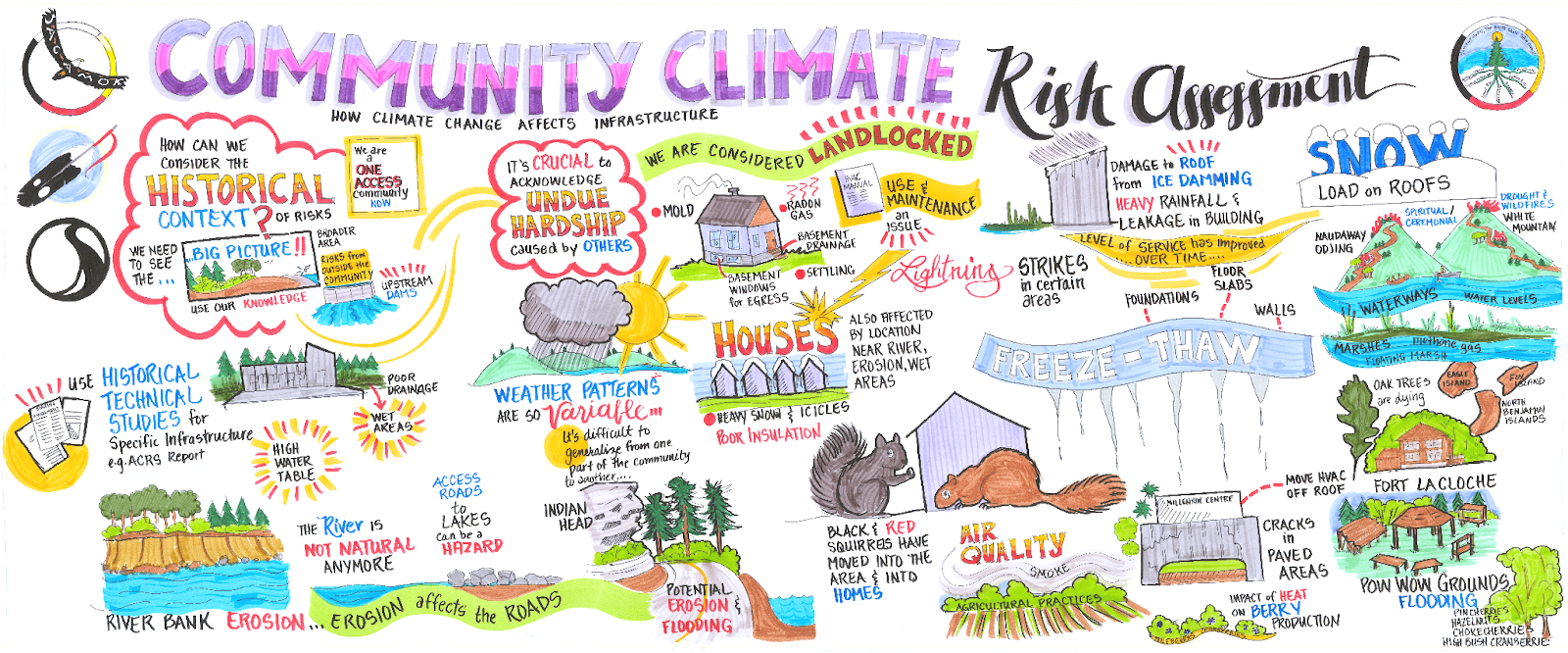

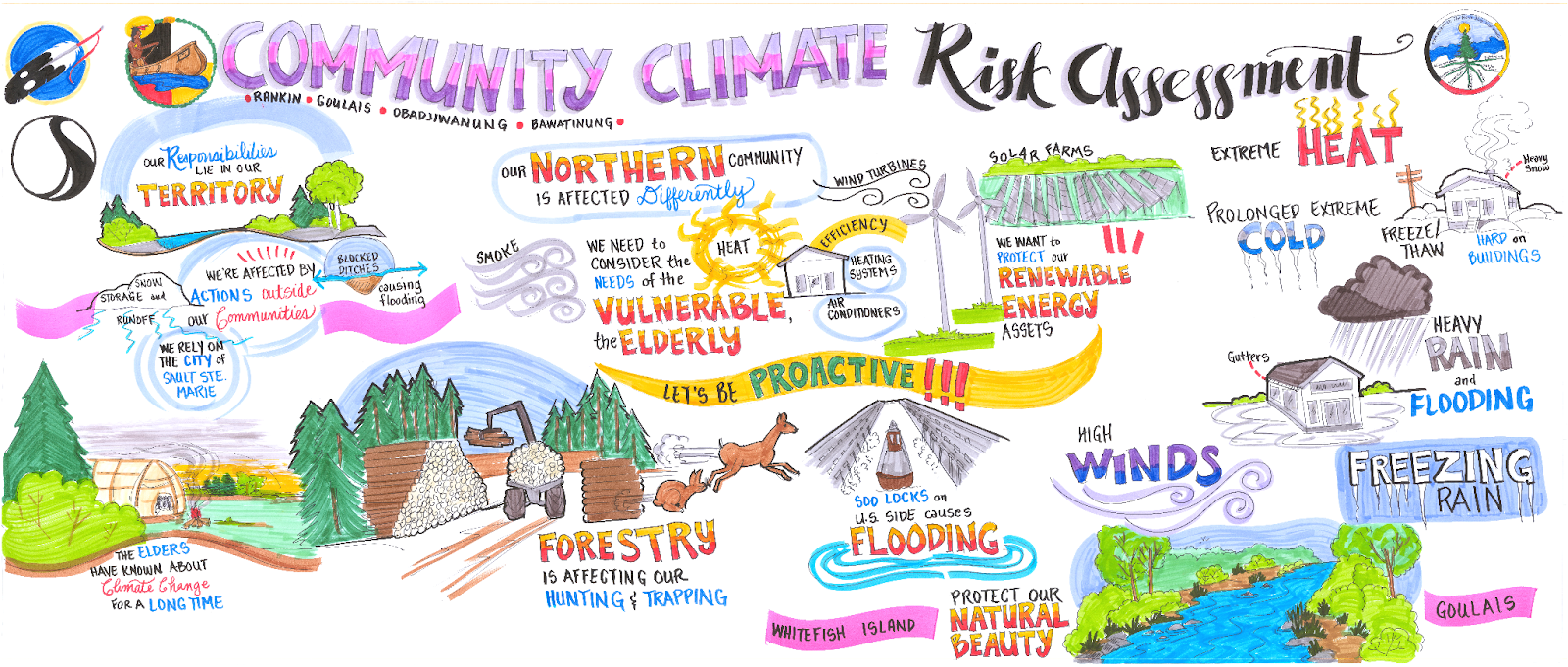

While the community members were recounting the changes they had witnessed and the central planning committee were discussing climate adaptation actions, Pamela Hubbard, a graphic recordist, shared space in the room, penciling in images and words onto a large canvas. Hubbard then pulled out a set of markers, and slowly the white and graphite canvas took on colour. The stories and observations of the community members, the climate risk assessment that was being tracked on a spreadsheet, and the actions the committee had come together to decide on, came alive on the canvas, their words transposed into murals.

At the end of the day, Lickers knows it’s more than putting something down on paper. It’s about recording and sharing their story. “I’m really excited that when this is all done, [we] get the opportunity to tell our story. Instead of a report, [where] the report gets put on the shelf and no one looks at it. Now we’ve got a story”

The climate risk assessment process that took place in Batchewana and Sagamok Anishnawbek was also documented on film. This media is used as an additional way to amplify voices and tell stories. The film offers a version of the process that includes the ideas and knowledges of people, shared in their own voices.

For the Future, The Next Generations

For Batchewana and Sagamok, their stories, ideas, and the planning process are captured in their action plan, the graphic recordings, and through video. But their stories don’t stop there. Joel Syrette speaks to the lasting effect of choices made long ago and the importance of thinking beyond the immediate future when making decisions.

“Bringing the community engagement part into the project was totally, totally rewarding. This is an example of bringing voices from communities across the province, if not across the country. That we are all working for the same objectives, and that’s for our future generations.” - Elmer Lickers

“The decisions that we make in our lifetime have an impact well into our future if you think about where we are in 2024, descending from one of those two headmen who signed that treaty in this community. My nieces and nephews, my namesake, are the 7th generation from him. And they are feeling the impacts of the decisions that he made, all the way back in 1850. And as we were somebody's thoughts 7 generations into the future.

At some point in our existence, we will be somebody’s ancestor that they look back 7 generations to, to say ‘wow my ancestors really thought of us in this time’. So in that, if we understand those fundamental concepts, that world view that's held within our language that also has an impact on us because it changes our way of thinking”

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) First Nations Communities and Planning for Climate Change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/first-nation-communities-and-planning-climate-change

.png)