The climate determines almost everything about how we design, build, and live in our cities. The streets and sidewalks, businesses and homes, parking lots and public transit that we use every day have been created to suit our climate. Now, with our climate changing, we need to re-think important aspects of how we live our urban lives.

Sadhu Johnston, Vancouver’s city manager, has spent many years doing hands-on work in urban sustainability in the USA and Canada. He says that facing up to the reality of climate change is vital for city planning and city living: “Change is happening, and we need to be prepared for that change.”

Over 80 percent of Canadians live in cities and towns. The dense concentration of people, government, business, infrastructure, and economic resources in urban areas makes them uniquely vulnerable to the growing risks of a warming world. This same density also makes cities a powerful source of resilience and resourcefulness when it comes to taking action on climate change.

And cities really do have to get prepared. Climate change presents city planners and dwellers with many risks and challenges. Gord Perks is a Toronto city councillor who has spent decades working on urban environmental issues. He notes that “all of our infrastructure is built for the wrong climate” and that most cities are “at the beginning stages” of figuring out how to best take action on climate change.

Fortunately, rising to the climate change challenge is also an opportunity to improve the health, safety, and quality of urban life. Johnston argues that building green economies and reducing greenhouse gas emissions has huge benefits for city life. “By doing these things,” he says, “you create these amazing urban environments that people want to be in, that people want to move their businesses to. It’s dynamic and exciting and interesting.”

The Prairie Climate Centre’s “Building a Climate-Resilient City” papers detail many steps that urban planners and populations can take to help adapt various aspects of city life to the worsening effects of global warming. Effective urban policy and design can and must minimize the impact of our growing urban population on climate change as well as help adapt to its consequences.

Disaster Planning

The 2013 floods in Calgary, the 2016 fires in Fort McMurray and the 2017 floods in southern Quebec demonstrated how incredibly expensive and damaging large-scale disasters can be for cities and the heavy toll they can take on residents.

Climate change means that we face a higher risk of more severe and more frequent disaster-level weather events such as floods and wildfires. It also increases the chance that multiple disasters could occur in a single season. The changing climate makes weather more variable as well as more extreme, which makes planning for disasters–and responding to them–much harder [1].

The Prairie Climate Centre prepared a series of reports on urban adaptation, resilience, and climate change for the cities of Calgary and Edmonton. Check out the report on disaster planning for measures that can improve community resilience and emergency management.

Health Risks: Heat & Pollution

Climate models indicate that many of Canada’s cities will experience dramatic increases in the number of hot days and nights as the climate continues to warm. These changes put city dwellers at a higher risk for heat stroke and heat exhaustion [2]. Toronto councillor Gord Perks notes that “We've been lucky so far that we haven't had a deadly heatwave, but that's a likely thing that will happen.”

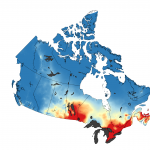

Our map of Tropical Nights shows that rising overnight temperature is another important consequence of climate change. In many places people can no longer count on night-time respite from summer heat.

The prospect of dangerously hot weather in Canada’s cities means we need to follow Toronto’s lead in planning for heat waves: the city uses a heat warning system to alert the population to elevated risk and operates a network of cooling centres to offer relief to vulnerable citizens.

More heat also means more pollution: high temperatures “bake” vehicle exhaust, turning it into harmful surface-level ozone and smog. This poses increased health risks [3, 4] and also makes the air very unpleasant to breathe. This is a good example where taking action to reduce health risks and promote wellness —such as creating more green space and urban forest cover—can also directly improve the quality of city life.

Read more about urban heat and air pollution in our article about the Urban Heat Island Effect.

Infrastructure

City life is highly dependent on services such as electrical power, drinking water, and transportation. All of these everyday necessities are vulnerable to changes in climate.

On Canada’s coasts, cities are vulnerable to rising sea levels, which bring with them the threat of flooding as well as more destructive storms and damaging waves [5]. Inland, changes in weather patterns and extremes could threaten cities with both too much water (in the form of overland or flash flooding) and too little water (in the form of extended periods of drought).

Communities in the north face a particularly difficult problem: they rely on stable, frozen permafrost for building and road construction. Global warming has already affected permafrost stability across the north, and continued warming will severely challenge municipal infrastructure and the roads, rail lines, and airports that provide essential links between the north and the rest of Canada [6].

All across the country, urban infrastructure faces the less dramatic, everyday threat of increased wear and tear caused by ongoing climate change. Engineers and designers build city infrastructure to suit local weather conditions. Shifts in averages and extremes of temperature or precipitation can exceed design expectations, shortening the effective life of the built environment. For example, higher temperatures can soften asphalt, making roads and bridges wear out more quickly.

Newly proposed design standards have started to take climate change into account, but have yet to be made an essential part of most urban planning. And of course existing structures and transportation links will require increased maintenance and extensive retrofitting to face the new climate reality.

Modern, climate-friendly approaches to designing and building these systems can reduce climate vulnerability while at the same time saving money, improving quality of life, and building more resilient communities.

Read in more detail about urban infrastructure issues in our report on urban resilience and the built environment.

Taking Action

The World Bank argues that “building cities that are green, inclusive, and sustainable should be the foundation of any local and national climate change agenda” [7].

Canadians who live in cities can take action on climate change on a personal level by making energy efficient choices and planning ahead for the most likely impacts of climate change where they live. Collectively, we can support and demand climate action from our business and political leaders, who have the power to make larger-scale change. “Ultimately we all have to be a part of the solution,” Sadhu Johnston says, “and by doing it we’re healthier and happier people with greater communities.”

Modern urban life in Canada is sustained by high-carbon sources of energy that cause global warming: we rely on fossil fuels for transportation, and much of our electrical power is generated by gas, oil, and coal. Given that over 80% of Canadians live in cities, efforts to reduce urban energy consumption while transitioning to renewable energy will have a dramatic impact on Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Transforming our energy systems has all kinds of advantages over and above helping with climate change. Climate-friendly energy systems will generate less pollution, provide more security, cause less environmental damage, and offer better quality of life. Johnston notes that “Vancouver is demonstrating to the world that cities can drive down carbon, and by doing so become more competitive and continue to grow.” He warns that “many people think there’s this dichotomy: that it’s either the environment and carbon reduction or the economy. There is a third way, and that’s bringing those two together and growing a green economy.”

Vancouver has made climate action a municipal priority as part of its commitment to become the “greenest city in the world”:

The process of ‘greening’ a city can have numerous offshoot benefits, among them increased resilience to the unavoidable effects of climate change. For example, revitalizing an urban forest can provide shade to residents during a heat wave, stabilize the soil, help sequester carbon from the air, and manage runoff and flooding during a rainstorm. All these effects help lower the city’s carbon footprint and prepare it to deal with more extreme weather.

Effective urban climate action ultimately requires both citizens and political leaders to commit to making change. Toronto councillor Gord Perks notes that both community groups and individuals have shown an amazing commitment to rising to the challenge of climate change. He says that “networks of creativity and commitment to a healthy future for our community are actually going to put us in a better place than we are today. We can wind up with better outcomes in terms of the quality of life; how you and your neighbours relate to each other; in terms of resilience and social ties. That's not just hopeful, that's exciting!”

References

- Feltmate, Blair. Climate Change and the Preparedness of Canadian Provinces and Yukon to Limit Potential Flood Damage.

- Berry, P., Clarke, K., Fleury, M.D. and Parker, S.. “Human Health.” in Canada in a Changing Climate: Sector Perspectives on Impacts and Adaptation

- Health Canada. “The Urban Heat Island Effect: Causes, Health Impacts and Mitigation Strategies”

- Daniel J. Jacob, Darrell A. Winner. “Effect of climate change on air quality.” Atmospheric Environment 43.1: 51-63.

- Natural Resources Canada. Canada’s Marine Coasts in a Changing Climate.

- Furgal, C., and Prowse, T.D. “Northern Canada.” in From Impacts to Adaptation: Canada in a Changing Climate 2007

- The World Bank. Cities and Climate Change: an Urgent Agenda

Further Reading

- Prairie Climate Centre: Building a Climate-Resilient City

- Prairie Climate Centre: Climate Change and Canada’s Cities

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Climate Change and Resiliency

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Working Group on Adaptation and Climate Resilience Final Report.

- 100 Resilient Cities

- UN Habitat. Cities and Climate Change. Guiding Principles for City Climate Action Planning.

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Canadian Cities and Climate Change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/canadian-cities-and-climate-change

.png)