More and more people around the world - particularly young people and those most affected by the impacts of climate change and related crises - are struggling to stay hopeful about the uncertain and changing future.[1] Living in this era of ‘wicked problems’ is impacting people’s mental health.[2]

For Winnipeg student Maria Farag, climate change makes it challenging to make plans for the future. “Usually when you make a plan, it’s because you have a future,” says Farag. “But if everything around you is already falling apart, what’s the point?” The nineteen year-old says she feels like she’s living in a “real-life post-apocalyptic movie”.

The stress many Canadians are feeling is normal - and, in fact, at times useful, in terms of motivating action - when facing an existential threat like climate change. For some, however, these challenges can be debilitating for their mental health given the complex emotions that can be experienced.

A Multitude of Emotions

Everyone will experience different emotions in response to climate change, and these emotions may also vary from day to day. Examples of these emotions include anxiety, depression, stress, fear, grief, guilt, sadness, anger, hopelessness and despair. Many terms have been suggested to encompass these climate-related emotions, such as climate anxiety, eco-anxiety, climate depression, or eco-grief.[3][4]

These emotions are experienced in varying levels of intensity. For example, being exposed to climate change information may cause discomfort and could push us to unconsciously stop reading about it to try to take one’s mind off the topic. For others, these emotions may become so intense it can paralyze them and affect their quality of life and ability to go about their daily routine.

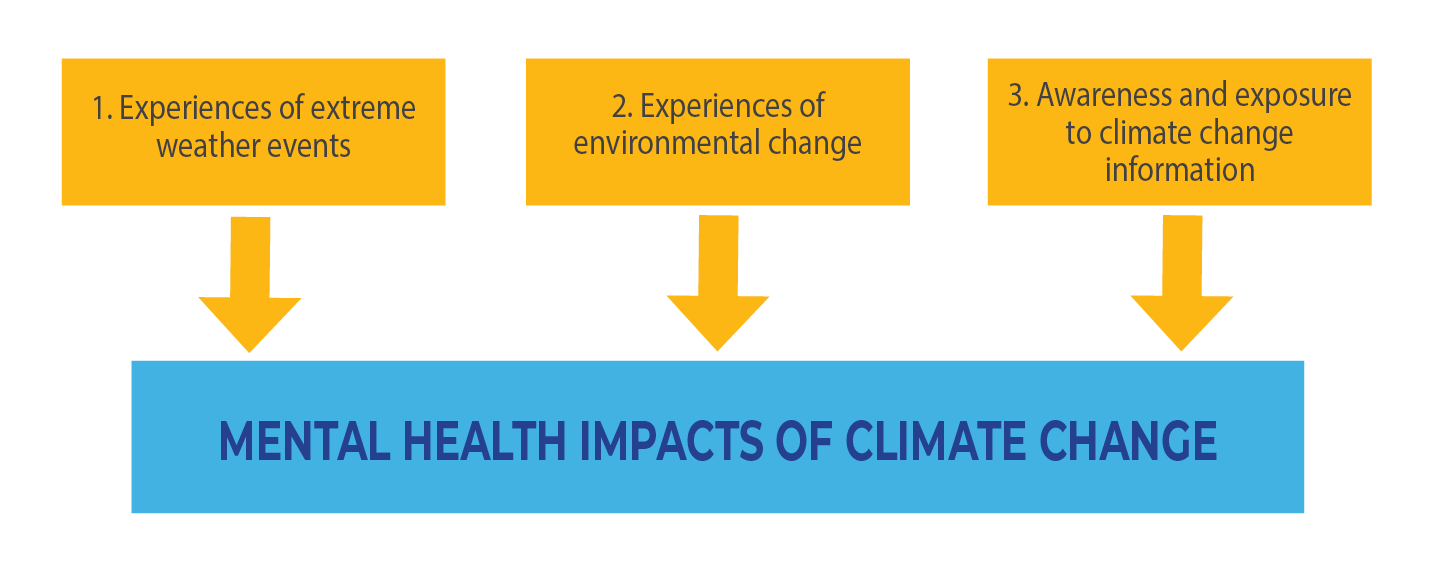

Three Pathways of Climate Mental Health Impacts

The mental health impacts of climate change can be categorized in three general pathways. A person may experience only one pathway or all of them simultaneously.

A summary of the three pathways in which climate change can impact our mental health.

1. Experiences of Extreme Weather Events

Directly experiencing climate-related extreme weather events, such as flooding, droughts and forest fires, can lead to mortality, morbidity, as well as impact mental health and well-being.[5] Extreme weather events can lead to loss of home, habitat, loved ones, injuries, loss of sleep, and other challenges which may in turn cause or increase anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress.[6] For example, after a recent flood in New Brunswick, residents reported experiences of intense stress, anxiety, exhaustion, worry and uncertainty.[7] Similar results have been found following wildfires in Alberta.[8] To take another example, an increase in heat is known to cause increased aggression, suicides, and hospitalizations due to mental health emergencies.[5] Those who already face health inequalities -- based on social, economic, and environmental factors -- are most at risk.[4]

2. Experiences of Environmental Changes

Another way that climate change can impact mental health is by experiencing and noticing gradual or sudden environmental changes, such as observing a close-by river drying up, disappearance of animals in a region, or changes in seasons. The loss of a ‘sense of place’ that these changes can cause is called ‘solastalgia,’ and contributes to anxiety and grief.[3]

People who spend more time outdoors and who have a stronger connection to the natural environment around them such as farmers, fishers, hunters, and outdoor enthusiasts may bear witness to these changes more frequently and intensely. This is particularly true for many Indigenous communities who remain closely connected to their lands, waters, and species within their traditional territories.

Read More: Environmental grief in Nunatsiavut

In Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Labrador, many residents have noticed climate change impacts in their environment, such as changes in weather and ice stability, and have expressed the effect that these changes have on their mental health.[9]

Scholar Ashlee Cunsolo Willox and her colleagues have collaborated with the community over a number of years to explore and document perspectives on climate change and the resulting health impacts, identifying mental health as a key issue. In a survey they conducted with the community, participating Elders and seniors felt that climate change was impacting their lifestyle (57%) and health (64%).[10] These changes affected residents’ daily activities, caused stress, and triggered a sense of loss of cultural identity and associated sense of home.

One major climate impact in the region is the decreasing reliability of ice, which makes it harder for people to get around, access cabins, and participate in traditional land-based activities. In the study, one male Elder described the resulting isolation and depression in the community: “I mean people, day after day after day look out the window and it’s this old, depressing fog and rain and wind. I mean it’s got to play on people’s minds."[10] People have expressed serious concerns about the rate of change in their territory and the threat it is posing to their traditional Inuit lifestyle. Despite these challenges, people within the community also expressed both a desire and knowledge regarding how to adapt and prepare for the physical, mental, and health impacts of a changing climate.

3. Awareness of Climate Change Information

Social contexts and networks play a significant role in how people internalize their understanding of climate change -- specifically the extent to which information is exaggerated or minimized. Interestingly and perhaps surprisingly, people who have supportive networks with reliable climate information may experience decreased mental health impacts than those who remain ignorant or in denial about climate change and its effects.[5] While denial may lower initial climate stress, it fails to address the cause of the issue, and therefore may increase the overall and long-term mental health burden for those you fail to acknowledge and address climate change.[5]

Young people - described as the ‘climate generation’ by some[11] – may be particularly at risk of experiencing these impacts, since many young people have never known a life without hearing about climate change and how it will adversely affect their future. Research indicates that the rapidly developing brain of children and adolescents, combined with their limited ability to avoid and adapt to climate stressors, may make children worry about climate change more than any other group.[12] A Winnipeg-based youth climate activist, Courtney Tosh, described climate change as a daunting threat that she thinks about constantly. “Everyday I’m scared… when I wake up and I don’t know what my future is going to look like,” says Tosh.

Climate-Related Distress is on the Rise

In Canada and around the world, we are seeing a rise in these emotions among all age groups, and region-specific responses will be required.[13] Child psychologist Dr. Michelle Warren has seen an increase in climate distress in her Winnipeg-based practice in the last 5 to 10 years. “It’s come up in the therapy of almost every child over the age of about 12 who has some degree of anxiety,” said Dr. Warren. “I would say once a week someone makes a very negative statement about the inevitability of climate change, and how ‘the world won't be here in 50 years anyways’.”

Adults are also having this experience. For Dustin Thiesen, a father, husband and former engineer, the distress he felt about climate change expressed itself in depression. After the birth of his child, he became increasingly worried about climate change. “It threw me into a pretty deep depression for the first time in my life,” he explained. “I got to the point where everything that I loved in life was ruined to me. It was a pretty dark time.”

Video: A Father's Experience of Climate Anxiety

Watch this video to find out more about Dustin’s story and how he coped with the mental health impacts of climate change.

Climate Anxiety Among White and Racialized Communities

While climate-related mental health challenges are on the rise, these challenges are not equally reported across different ethnic groups. Some experts have observed that climate anxiety is more commonly reported among white people than racialized communities. As scholar Sarah Jaquette Ray writes, this is likely in part because Black, Indigenous, and other people of colour (BIPOC) have faced existential threats to their ways of life for generations, through colonialism, slavery, and ongoing racism.[14] Potawatomi scholar-activist Kyle Whyte describes climate change as “an intensification of environmental change imposed on Indigenous peoples by colonialism”.[15] These communities have long histories of resistance and persistence through which they have developed ways to cope with difficult emotions - such as fear, anger, and anxiety - that arise in the face of existential threats.

In contrast, for many white communities, it is new to face an existential threat - such as climate change - and this challenges their sense of safety and future opportunity and thereby raises difficult emotions.

Considering these different experiences, it is particularly important that white people not let these emotions paralyze them, or feed into ideas of racism or xenophobia.[14] Rather, they have a particular responsibility to find coping mechanisms and opportunities to channel these emotions into actions for the benefit of all. White communities can also listen to and learn about strategies from the experiences of BIPOC people.

Importantly, it is essential not to conflate experiences of climate anxiety with broader impacts and concern regarding climate change, the latter of which has been found to be higher among racialized communities.[16] Indigenous and other racialized communities stand to be disproportionately impacted by climate change due to societal structural inequalities.[17] And given that Indigenous traditional ways of living have not contributed to current fossil-fueled climate change, when Indigenous peoples are mischaracterized as being part of the problem and/or are disregarded in discussions of solutions, it can pose serious psychological harm. As Ingird Waldron, author and expert on environmental racism, writes, “in order to develop more robust and equitable climate policies, it is important that decision makers understand how climate impacts, environmental racism, and structural determinants of health intersect to shape health and well-being, especially in Indigenous, Black, and other racialized and marginalized communities.”[18]

Learning to Work with Distressing Emotions

Anxiety and distressing emotions are normal responses to complex existential threats. For example, if we see a bear in the forest while hiking, it is normal to experience sudden anxiety and fear, as that allows us to choose the best course of action to survive. Climate change is another example of a threat that triggers this anxiety, fear, and survival response.

That said, climate change is global and long-term, so we must learn to cope with the difficult emotions arising in response to this existential threat otherwise these emotions can overwhelm, preventing us from participating in solutions. If you are experiencing significant distress due to climate change, it’s important to consider seeking support from mental health professionals.

Read More: Channeling our fears into action

Coping with these difficult emotions is key to enabling us to take action on climate change. In the words of Canadian author and activist, Naomi Klein, in her book This Changes Everything:

“What should we do with this fear that comes from living on a planet that is dying? [...] Use it. Fear is a survival response. [I]t can make us act superhuman. But we need somewhere to run to. Without that, the fear is only paralyzing. So the real trick [...] is to allow the terror of an unlivable future to be balanced and soothed by the prospect of building something much better than many of us have previously dared hope.”[19]

We cannot deny that we are already facing climate change impacts, and that we are already locked in to worsening impacts in the decades to come. But, as Klein outlines, we can still avoid the worst and pursue better possibilities, and that is worth fighting for. “All I know,” she writes, “is that nothing is inevitable. Nothing except that climate change changes everything. And for a very brief time, the nature of that change is still up to us.”[19]

The challenge is to recognize and work with these rational but difficult emotions, to turn them into action towards a better future. For more information on how to take action, see our Taking Action on Climate Emotions article, which explores the various ways that people and communities can adapt to climate-related distress and support building positive, vibrant, and sustainable futures for all.

Further Readings

- BBC Climate Emotions Column: https://www.bbc.com/future/columns/climate-emotions

- Gen Dread: A Newsletter for “staying sane in the climate crisis” https://gendread.substack.com and “Resources for working with climate emotions” https://gendread.substack.com/p/resources-for-working-with-climate

References

- Taylor, M. & Murray, J. (2020, Feb 10). Overwhelming and terrifying’: the rise of climate anxiety. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/10/overwhelming-and-terrifying-impact-of-climate-crisis-on-mental-health

- Hayes, K., Blashki, G., Wiseman, J. et al. (2018). Climate change and mental health: risks, impacts and priority actions. Int J Ment Health Syst 12, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0210-6

- Albrecht, G. (2019). Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World. Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Pihkala. (2020). Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12197836.

- Ebi et al. (2021). Extreme weather and climate change: Population health and health systems implications. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 293-315.

- Clayton, S. (2021). Climate Change and Mental Health. Current Environmental Health Reports. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33389625/

- Woodhall-Melnik, J., & Grogan, C. (2019). Perceptions of mental health and wellbeing following residential displacement and damage from the 2018 St. John river flood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214174

- Brown, M. R. G., Agyapong, V., Greenshaw, A. J., Cribben, I., Brett-MacLean, P., Drolet, J., McDonald-Harker, C., Omeje, J., Mankowsi, M., Noble, S., Kitching, D. T., & Silverstone, P. H. (2019). Significant PTSD and Other Mental Health Effects Present 18 Months After the Fort Mcmurray Wildfire: Findings From 3,070 Grades 7–12 Students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 623. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00623

- Cunsolo, A., Harper, S. L., Ford, J. D., Edge, V. L., Landman, K., Houle, K., Blake, S., & Wolfrey, C. (2013). Climate change and mental health: an exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Climatic Change, 121(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0875-4

- Ostapchuk, Harper, Cunsolo Willox, Edge, and Community Government. (2015). Exploring Elders’ and Seniors’ Perceptions of How Climate Change Is Impacting Health and Well-Being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut / ᕿᒥᕐᕈᓂᖅ ᐃᓐᓇᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᑐᖃᐃᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᔾᔪᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᕆᒍᓚᑦ, ᓄᓇᑦᓯᐊᕗᒻᒥ ᓯᓚᐅᑉ ᐊᓯᔾᔨᐸᓪᓕᐊᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᑦᑐᐃᓂᖃᖅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᐃᓗᓯᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᓄᐃᓐᖏᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ. International Journal of Indigenous Health 9:6. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijih92201214358.

- Jaquette Ray, S. (2020). A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. University of California Press.

- Vergunst, F. & Berry, H.L. (2021). Climate change and children’s mental health: A developmental perspective. Clinical Psychological Science. DOI: 10.1177/21677026211040787

- Majeed, H. & Lee, J. (2017). The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health. The Lancet Planetary Health, 3, E94-E95.

- Jaquette Ray, Sarah. (2021). Climate Anxiety Is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-climate-anxiety/

- Whyte, K. (2017). Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene. English Language Notes 55.1: 153-162.

- Ballew, M., Maibach, E., Kotcher, J., Bergquist, P., Rosenthal, S., Marlon, J., and Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Which racial/ethnic groups care most about climate change?. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

- Versey. (2021). Missing Pieces in the Discussion on Climate Change and Risk: Intersectionality and Compounded Vulnerability. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Vol. 8(1) 67 –7

- Waldron, I. (2021). Environmental Racism and Climate Change: Determinants of Health in Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian Communities. Canadian Institute for Climate Choices. https://climatechoices.ca/publications/environmental-racism-and-climate-change/

- Klein, N. (2015). This changes everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. Simon and Schuster. P.28

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Mental Health and Climate Change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/mental-health-and-climate-change

.png)