For decades Inuit have been leading the conversation on climate change in Canada. Inuit writer and advocate Siila Watt-Cloutier has been at the helm of this work. “As Inuit, we rely on the cold, the ice, the snow. That is our life force,” she says. For her people, the cold and sea ice are at the center of culture, transportation, safety, health, and education. Climate change is impacting the Inuit way of life.

See More: Siila Watt-Cloutier and the importance of sea ice for Inuit

As such, many Inuit Elders and hunters are concerned by accelerated changes to the land, water, weather system, and wildlife. They are experiencing things outside of the range expected or observed in oral histories.[1] These observations are obvious in Qapirangajuq: Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change, the first feature-length film about climate change in Inuktitut, directed by Dr. Ian Mauro & Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk. Elders and hunters from across Nunavut contributed to the film and were particularly vocal about the threat of climate change to economy, food security, and culture.

Read More: Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) translates into English as “things we have always known” (Owlijoot, 2008), or “what Inuit have always known to be true” (Karetak, Tester, & Tagalik, 2017). IQ embraces all aspects of Inuit culture, including values, worldview, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions, and expectations (Government of Nunavut, 2007). This system of knowledge and values is a dynamic, situational, and on-going process that has been developing over thousands of years that Inuit have lived in Arctic environments.

In 2016, building on long-term relationships with the community of Pangnirtung, Nunavut, Dr. Ian Mauro was invited with Prairie Climate Centre Master’s student Natalie Baird to develop a community-based research project centred on visualizing changing oceans through video. Pangnirtung ( “Place of many bull caribou” in inuktitut) is a remote coastal community rich in natural marine resources.

Map of Pangnirtung, Nunavut

The research used collaborative video to work with local experts to document and share knowledge related to the ocean. Pangnirtung has commercial Arctic Char and Greenlandic Halibut fisheries that are an important source of income and pride for the community. Many fishers are observing changes to local fish species, as well as changes to ice conditions and weather patterns. However, many people remain hopeful that the fishery will be able to respond and adapt to changes.

See More: Fishing With Our Hands in Pangnirtung, Nunavut

Through interviews and conversations, many people highlighted the need to support youth and intergenerational knowledge sharing as key to resilience. As fishermen and community leader Johnny Mike shared,

“As we are living in the Arctic, we are at the frontlines to witness the change. Younger generation will be facing much more climate change than we can see today.”

Young fisherman Sean Kullualik on a fishing trip in Cumberland Sound.

Engaging youth through arts-based research

Youth are facing the challenges of a changing climate, however, they are often left out of the conversation. In response, many have called for research that engaged youth through mentoring and training, such as the National Inuit Climate Change Strategy that advocates for research that is hands-on, on-the-land, and connects youth and Elders.

One opportunity is through visual arts. Across Nunavut there is a large artistic cultural economy, including carving, printmaking, textile arts, and filmmaking. In Pangnirtung, visual arts play material, cultural, and therapeutic roles – as important income for families, a tool for embedding traditional knowledge into art objects, and a means to heal and build strength. As the late Pangnirtung Elder Elisapee Ishulutaq shared, “I make prints so the next generation would know who I was and what I have gone through.”

Artists and art-making have the ability to connect people with shared histories and cultivate stories of resilience. In recent years, climate change researchers and communities have started using art as a way to connect across cultures and generations.

As part of her Master’s research, Natalie Baird partnered with local filmmaker David Poisey to facilitate video, photography, and storytelling workshops for youth in collaboration with the Pangnirtung Youth Centre and Attagoyuk Ilisavik High School. Natalie and David lead participants in planning, producing, editing, and sharing digital media narratives, in both English and Inuktitut, the Inuit language. Youth and Elders came together in community and on-the-land to create digital narratives related to the importance of the land and water for identity and well-being.

See More: Elder Joanasie Qappik’s shares his observations of climate change

Pangnirtung filmmaker David Poisey has long been an advocate for video as a tool to document Inuit oral histories and preserve language.

The importance of sea ice and sea water for youth

In September 2017 Natalie and David worked with Attagoyuk Ilisavik staff and students to lead a photography workshop with grade 10 and 11 science students. Students built simple pinhole cameras out of recycled materials and experimented with exposure times and darkroom photography.

Read More: How to make a coffee tin pinhole camera

Making your camera

- Using a hammer and nail, make a 1cm hole in the middle of the coffee tin wall.

- Paint inside of tin with matte-black paint. Let dry. If your tin has a transparent lid, paint it as well.

- Cut 5x5cm inch of aluminum from a pop can. Using a size 10 beading needle, carefully make your pinhole in the middle of the aluminum square. Sand both sides of aluminum piece to remove any shards. Wash off dust and let dry.

- On the outside of the tin, line up your aluminum pinhole with the hole in the coffee tin. Tape down the aluminum with electrical tape, ensuring the edges of the aluminum are lighttight.

- Place a piece of tape over your pinhole – this is your shutter.

- Examine your camera and be sure it is lighttight. You may need to add additional electrical tape to the edge of your tin’s lid.

Loading your camera

- In the darkroom, load your camera with light sensitive paper, ensuring the paper is directly across from the pinhole, emulsion side up. You may want to tape the paper to the wall of your camera so it doesn’t move around. Close your camera.

Testing your camera

- Your camera will have a 30 second exposure in bright, direct sunlight. Depending on the conditions (cloud cover, time of day, shade) you may need to add time to your exposure. - Do a test to ensure your camera creates a good exposure in 30 seconds. Set up your camera in a location where it will remain still.

- Arrange your photograph. For portraits, place your camera at least 1 meter from your subject.

- Set a timer for 30 seconds – do not count in your head. When you are ready, open your shutter for 30 seconds. When the timer goes off, close your camera promptly. Do your best to not move the camera at all during the exposure time.

Developing your negative

- In the darkroom, open your camera and process your negative print using the paper processing trays.

- Assess the exposure of your camera and adjust your exposure time accordingly.

- Negative has good distribution of whites, black and greys: good exposure! Take more pictures using the same exposure time and in the same light conditions.

- Negative is very bright: your photo is underexposed and the positive print be very dark. Expose for more time (try in 10-30 second increments)

- Negative is very dark: your photo is overexposed and the positive print be very bright and faint. Expose for less time (try in 10-30 second increments)

- Negative is grey and has no visible image: your camera may have a light leak, or your paper somehow became exposed to light. Examine your camera, tape up any leaks, and try again.

- Hang your print to dry and re-load your camera.

Printing your positive

- To develop a positive print of your negative, either contact print your negative using the enlarger in the darkroom or scan the negative and invert the image in Photoshop.

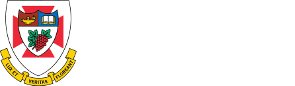

Next, the students took to the shoreline to create photos based on the question: “Why is imaq (sea water) and siku (sea ice) important to youth?” Their photographs connect the importance of the water and sea ice to land-based activities and how these activities relate to and reinforce identity and well-being.

The pinhole camera construction allowed students to both engage and understand camera construction and light science, and then put these techniques into action to reflect on the research question.

Youth pinhole photographs and reflections on the importance of sea ice and sea water.

The short film Tariuq Takujannik / The Ocean From My Eye brings together the workshop process and photographs in conversation with voices from Pangnirtung, weaving together multiple technologies, generations, and languages.

Watch Tariuq Takujannik - The Ocean From My Eye, youth perspectives on climate change through the lens of pinhole photography.

Because of the unique qualities of the short films and photographs, this project has been shared extensively online and through academic conferences and film festivals. The research team continues to collaborate with Pangnirtung youth, hunters, and Elders to explore climate change, health, and well-being through partnerships with ARCTIConnexion and the Hamlet of Pangnirtung.

Pinhole photograph of students outside Attagoyuk Ilisavik in Pangnirtung, Nunavut

Recommended Article Citation

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Visualizing Changing Oceans through Collaborative Research in Pangnirtung, Nunavut. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/visualizing-changing-oceans-through-collaborative-research-pangnirtung-nunavut

.png)